An historian has declared that the three most written-about subjects of all time are Jesus, the Civil War, and the Titanic.

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912, the question arises, “Why can we not let go of that ‘tragic’ event?” April being also Civil War History Month, I am sadly reminded of the cruel irony of the fact that Americans little noted nor have long remembered the worst maritime disaster in United States history, the sinking of the SS Sultana, its losses greater than the Titanic, raising the question, “Why have we not taken hold of the Sultana?”

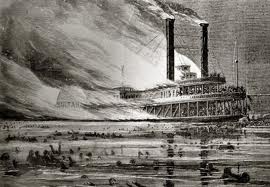

As our Coast Guard conducts its annual commemoration of the sinking of the Titanic, as London observes the centennial of that event, and as the movie Titanic returns to the screen in 3D to enthrall audiences worldwide, Americans, deep into the Civil War Sesquicentennial’s second year, are almost totally unmindful of the Sultana’s some 1,800 casualties–union soldiers, recently released from Andersonville and other Confederate prisons, and civilians, including women and children–who perished April 27, 1865 at 2 am, in darkness, in a cold rain, in the Mississippi River just above Memphis, as the assassinated President’s funeral train was crossing the United States.

An estimated 1,800 perished when the Sultana exploded, compared with the Titanic’s 1,523. More military passengers were from Ohio, 652, and Tennessee, 463, than from other states. About 800 survived, about 300 of whom later died of burns and exposure.

Among survivors who lived long lives afterward was Daniel Allen, from Sevier County, who testified in 1892, “I pressed toward the bow, passing many wounded sufferers, who piteously begged to be thrown overboard. I saw men, while attempting to escape, pitch down through the hatchway that was full of blue curling flames, or rush wildly from the vessel to death and destruction in the turbid waters below. I clambered upon the hurricane deck and with calmness and self-possession assisted others to escape.”

In my hometown Knoxville, in divided East Tennessee, the survivors met in April each year, including 1912, twelve days after the Titanic sank, until only one veteran showed up in 1930. July 4, 1916, survivors dedicated an impressive monument in Mount Olive Baptist Church Cemetery, 2500 Maryville Pike.

Writers have derived a plethora of meanings from the Titanic legacy, but in a very general context; the Civil War context for the unexamined symbolic relevance of the Sultana legacy is painfully specific, for as Shelby Foote said, “The Civil War is the cross-roads of our being as a nation.”

Despite the publication over the years of books about the Sultana, most Americans still have never heard of it. The first was Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors (1892) by Chester D. Berry, a survivor, (reprinted in 2005 by the University of Tennessee Press). Seventy years later James W. Elliott’s Transport To Disaster (1962) appeared; Jerry Potter, Memphis lawyer, published The Sultana Tragedy thirty years later. Not even Jim Brown’s excellent article in the News Sentinel two decades ago left a lasting impression on East Tennesseans.

But in 1987, Knoxville attorney Norman Shaw, not a descendant, started the Association of Sultana Descendants and Friends, whose newsletter is called Sultana Remembered. They have met annually in Knoxville, Memphis, Cincinnati, and other relevant cities.

The rest is silence.

No rich celebrities were among the estimated 2,400 passengers who boarded the Sultana, a boat built for only 376, over-loaded in a conspiracy of greedy civilian and military men. No iceberg-like external force ignited the explosion of four boilers known to be defective. No divers descend now to gaze upon a sea-preserved ship worthy of exhibition in replica at Dollywood, because the “Muddy” Mississippi shrugged its shoulders and moved into other channels, leaving the SS Sultana and its victims under mud where now a soybean field thrives.

Thank you for your column on the Sultana. I have always been curious why this aspect of the war never received more attention. My great grandfather, Pleasant Lafayette Atchley of Sevierville, somehow survuved the wreck, claiming, according to family lore, that he “swam seven miles” to safety. Captured at Fort Athens, Alabama, by Gen. Forest when the company commander purportedly was tricked into surrendering the fort, Fate spent the remaining months of the war in the Cahawba prison. He lived until 1910. My father, who died at 101 in 2008, remebered his grandfather and his disappointment with his Civil War experience. He purportedly remarked, “If I had it to do over again, I would have fought for the South!” Anyway, I am glad he made it.

Thank you for augmenting the story of the Sultana. Your ancestor tells his own story in LOSS OF THE SULTANA AND REMINISCENCES OF THE SURVIVORS [repinted by UT Press with my long introduction].

Please come by Blount Mansion, Gay St. entrance, for the opening of Civil War sites in Knoxville tours, so I can meet you and learn more. In any case, stay in touch because we of the East Tennessee Civil War Alliance want to collect such stories for researchers. Later on, could we interview you?

Mr. Madden,

My Great, Great Grandfather William Wooley, Company I, 6th Kentucky Cavalry Union Forces. He was lost onboard the Sultana when it went down. He left behind 2 small boys and a young wife. I also lost 2 Great Grand Uncle’s. Henry Huddleston and Charles Tucker. In the book “Loss Of The Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors” it leaves out 9 soldiers of Company I, 6th Kentucky Cavalry and are as follows. George Dabny (Dabney), Pvt., James Hall, Sergent., Henry T. (S) Huddleston, Pvt., Stephen Jones, Pvt., Francis McDaniel (McDonald), Pvt., James McDaniel (McDonald), Pvt., Charles Moary, Pvt., George Tucker, Corporal, William Wooley, Pvt. These men suffered Cahaba Prison for a short time and then Sultana. These men deserve to be remembered.

It wasn’t until the 1980’s that I found out my Gr. Great Grandfather William was on the Sultana. All my Grandfather knew is that he died on a boat on the Mississippi River coming home. Gr.Gr. Grandpa’s Civil War picture hung in my bedroom during my childhood and still does today.

James Wooley

Mr. Madden,

In my hast I left out some soldiers of Company I, 6th Kentucky Cavalry Union Forces aboard the Sultana. They are as follows: Abraham Rodes, Pvt., Henry Johnson, Sergent, William Oaks, Pvt., James Parker, Pvt.

and James McDonnell, Pvt. (Could be the same man as James McDaniel (McDonald.)) and S.W. Jones, Pvt., (Could be the same man as Stephen Jones, Pvt.. These men also deserve to be remembered.

James Wooley

Mr. Wooley, I am very glad to hear from you and have all that excellent information, which I will add to my trove. I hope to get back to you soon and share with you the many emails I have gotten in response to the article. David

Further research shows that Henry T. (S.) Huddleston was released from the hospital at Memphis, but was not on the Sultana. James W. McDaniel and his brother Francis are really MacDonald’s not McDaniel. They are list in the Adjutant General’s Report for Company I, 6th Ky Cav as McDaniel. I know the family. William Oaks is not listed on the Adjutant General’s report for Company I, 6th Kentucky Cavalry, but is listed in Jerry Potter’s book “The Sultana Tragedy”?

James Wooley

These men were captured April 1, 1865, at Trion, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, by elements of Forrest’s cavalry under Brigadier GEnreal William H. Jackson. They were taken to Marion, Alabama, before being transported by rail to the stockade at Meridian, Mississippi. Twelve of the thirty men captured from the Sixth Kentucky Cavalry that day died aboard the Sultana.

Henry T. (should be S.) Huddleston was onboard the Sultana. He was listed as being in Company H, 6th Kentucky in Jerry Potter’s book. In reality he was in Company I, 6th Kentucky Cavalry, USA. I thought I had it right to start with. I was to fast to correct myself not wanting to put out false information. Sorry!

James Wooley

Many of those men in the Sixth Kentucky Cavalry U.S., including their commanding officer, Major William Fidler, were captured on April 6, 1865, at Pleasant Ridge, Greene County, Alabama. Heretofore little has been published on this skirmish between the Federal cavalry brigade of BG Croxton and the Confederate command of BG W. Wirt Adams, until I began to examine the fight and found much new information. My research is published in The Alabama Review 62 (2) April 2009: 83-112.

http://magnolia.cyriv.com/GreeneAlGenWeb/Military/CSA/SipseySkirmish.asp