originally published in the Knoxville News Sentinel (Nov 30, 2014)

Last week we celebrated Thanksgiving, proclaimed a national holiday by Abraham Lincoln, and on Nov. 19 we marked the 151st anniversary of the Gettysburg Address. As we approach the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, I am mindful of the many ways Americans have always missed the war.

In the several decades after the war, men, women and children saw more and more of the artists’ and finally the photographers’ scenes, and read the memoirs of the generals and officers, and heard the memorial speeches, and perhaps read the 128 volumes of “The Official Records of Union and Confederates Armies.”

Americans stored them up, mulled them over, and then began the long forgetting, made more painful in the South by the punitive Reconstruction that Lincoln had planned to avoid. And still, each and all missed the war, because it all sifts down finally to little more than fragments found on the field.

Then over the years, into the next century, into the hands of Americans came more and more of the common man’s accounts, views from the battlefields, the hospitals, the prisons. And more and more came the perspectives from the home front, the refugee’s, the widow’s, the spy’s, the mother’s, the nurse’s perspectives.

And still, pervading all those testimonials is that nagging apprehensiveness that drove Lincoln to the telegraph office, feeling that he was missing the war.

But what of the historians and the biographers, trailing along behind, collecting, arranging, filling in background? The fragments have insisted on remaining fragments. With so much missing, the whole, the vision of the whole, has remained unachieved.

Americans missed the war that most shaped America’s destiny by remaining mesmerized by the fragments they picked up, isolated handfuls of facts about battles and leaders mostly. The public, from generation to generation, remained obsessed with the role of ancestors or with the look of artifacts, those literal fragments — swords, guns, bullets, uniforms, flags — found on the field.

In the two hours he wandered the battlefield that morning in Gettysburg, Lincoln witnessed scavengers thrilled to pick up, possess and count the value of fragments.

Americans have been immersed in seemingly endless talk, an endless stream of books, endless novels and poems that repeat and repeat and repeat the same things, as if damned to seek knowledge, understanding and perhaps even the vision in the self-same icons, tokens, runes and ruins.

The painful paradox is that both the men who fought and all people who have read about the battles missed the war. For the war is not only the details of battles such as Gettysburg and the simultaneous battle of Vicksburg, but a deeper exploration of the meaning of the whole war that would reveal itself in each individual American from the day of Lincoln’s address to this very day.

Americans have failed to make the nature of this war and its lessons part of their everyday lives as they deal with America’s problems. Let our vision henceforth be not to celebrate the war as an interesting time in history but to meditate on the war as a motive and prelude to action.

Let us look at the war through every conceivable perspective. Implore nurses, lawyers, physicians, journalists, dentists, teachers, merchants, laborers of every type, scientists of every type, engineers, geographers, secretaries, politicians, architects, women, ethnic groups to look at the war from their points of view and meditate on, talk about and publish their visions.

“The great task remaining before us” — to use Lincoln’s words — is to achieve at long last an understanding of the war commensurate with its lasting effects: the dark problems and bright prospects for America that came out of the war. Let us examine all aspects of the war in such a way as to pursue solutions to the problems that remain with us today — violence, racism and mistrust of government.

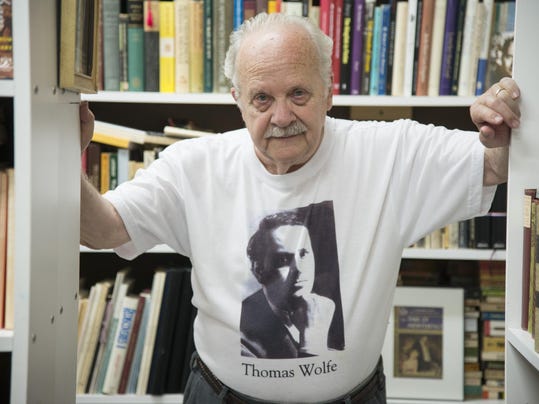

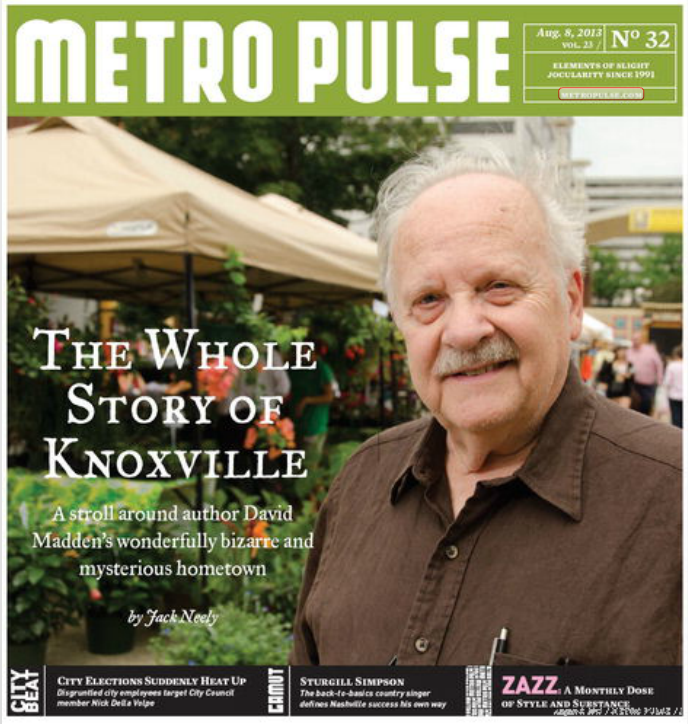

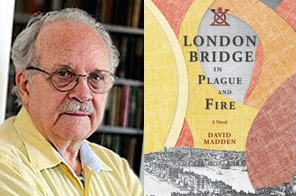

David Madden, a novelist and Civil War historian, is a native of Knoxville who lives in Black Mountain, N.C.